Behavioral origins of distinctions in employees’ attitude towards corruption

Abstract

Purpose. The study examines the behavioral determinants that explain why successful and well-paid employees may become involved in corrupt practices. It aims to identify how attitudes toward corruption differ across age groups, education levels, occupations, and subjective economic status among employees working in the Russian Federation. Methods. The research is based on Descriptive Decision Theory as the conceptual foundation for explaining regularities in individuals’ choices. It employs a mixed-methods design, including semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and surveys, with a sample of 256 respondents employed in the Russian Federation (not all of Russian origin). The data were analyzed through thematic analysis as the primary ethnographic method. Given the size and heterogeneity of the Russian labor market, the sample used in this study requires additional clarification regarding its representativeness. The 256 respondents included in the research do not claim to statistically represent all employees in the Russian Federation; rather, they form a purposive sample focused on capturing behavioral patterns among economically active, legally compliant, and socially integrated workers – groups most relevant to analyzing the paradox of corruption among successful employees. Accordingly, the general population for the study is intentionally narrowed to employed individuals with stable income and established career trajectories, which allows for a more accurate examination of behavioral factors influencing attitudes toward corruption. This approach ensures conceptual, rather than statistical, representativeness by aligning the characteristics of the sample with the theoretical objectives of the research. Results. The findings reveal distinct patterns among several groups: youth and middle-aged employees, private-sector and government workers, individuals with higher education and those holding scientific degrees. Behavioral features associated with Prospect Theory – such as anchoring, loss aversion, and risk-seeking – serve as explanatory mechanisms for differences in corruption-related attitudes. This study addresses the central paradox that successful, socially integrated and well-paid employees – individuals who, according to classical economic and legal assumptions, have the least incentive to engage in corruption – are nonetheless vulnerable to corrupt behaviour. This challenges the traditional view that corruption is primarily driven by economic need or lack of resources. Instead, it suggests that behavioral factors, cognitive biases, and situational perceptions may outweigh rational cost-benefit calculations. It is essential to identify and explain this contradiction in order to understand why corruption persists, even among those who seemingly have the most to lose. Scientific significance. This study represents the first research of this type using Russian empirical data while integrating behavioral insights with national legal norms and regulatory practices. It provides an interdisciplinary perspective on how human behavior, convenience, facilitation, and productivity interact within corruption contexts. The results offer guidance for designing future regulatory measures aimed at reducing corruption levels.

Introduction. Corruption has been a field of microeconomic studies for many years. Corruption is viewed as a global issue. The growth of multinational companies and numerous cases of corruption among their top managers (Pond, 2018) have contributed dramatically to the global nature of corruption, stimulating interest in the study of corruption among well-paid employees. In 2011, Transparency International prepared the Bribe Payers Index (Transparency International, 2011). The study of Transparency International referred to 28 states and 19 sectors of the economy. The countries enumerated in the index represent 80% of world exports of goods and services. According to this index Russian companies are among the top corrupted in foreign operations as well as China. Therefore, the studies of top-managers corruption in these countries can be of a particular interest.

Most of the publications on the corruption traditionally were based on the assumption that individuals are rational in the standard economic sense and they maximize their expected utility function when making choices (Winter, 2017). However, recently, the expected utility paradigm has been questioned by the behavioral economics literature (Kahneman, 2003; Thaler, 2016) and a new notion of rationality was developed (Smith, 2003).

The current behavioral economics literature seems to agree mostly with the prospect theory model of behaviour (Wakker, 2010; Barberis, 2013) which seems to be applicable for different cultures (Bruhin et al., 2010; Povetkina et al., 2020). Prospect Theory has different dimensions. Firstly, individuals evaluate outcomes of decisions with a value function that is not linear. This value function taken in isolation indicates risk aversion on gains with respect to the risk seeking on losses. Secondly, individuals transform probabilities of outcomes into subjective decision weights. Finally, individuals treat different risky decisions independently, a feature called mental accounting.

The application of those approaches to law and economics has led to a new field called behavioral law and economics (Wright & Ginsburg, 2012). There are studies (Dupuy& Neset, 2018) which especially focus on the cognitive psychology of corruption. One of the main puzzles is why despite anti-corruption campaigns, some countries have made little progress on reducing corruption (Heywood, 2017; Rose-Ackerman & Palifka, 2016). Some studies (Zaloznaya, 2017; Hoffman &Patel, 2017) focus on group norms influencing unethical behaviour. Our aim is to focus on individual behavioral aspects which may influence corrupted decision making. The prospect theory influence on corrupted behavior is understudied although the prospect theory is proved empirically more than other theories about the models of decision making. This study fills this gap and analyses corrupted behavior with special reference to this theory.

The risk of severe liability for corrupted person is very high. Still well-educated people with descent salaries and well-established position in the society tend to be corrupted. This study identifies the specific psychological mindset of top managers of private and public legal entities who are involved in corruption. The study maps it onto prospect theory features, such as loss aversion, risk-seeking and anchoring. Although the results of this research are based on selected countries, they are also relevant to others.

The sources of the research were studied in the archives of the State Library of the Russian Federation, OECD library, funds of the National Library of the Russian Federation, scientific library of the Moscow State University and the President Library.

To strengthen the analytical rigor of this study, it is important to recognize that the topic under investigation is highly sensitive, which increases the likelihood of response distortions caused by social desirability bias. As Russian scholars such as M. Yakovlev and A. Klimenko have noted (Gans, Morse & al., 2021), surveys that address corruption-related issues are systematically affected by respondents' tendency to provide socially acceptable answers, underreport their own involvement and exaggerate their normative attitudes. This factor is particularly relevant when interpreting comparisons across groups. For instance, the responses of younger participants may reflect not lower tolerance for corruption per se, but rather their limited real-life exposure to corrupt practices and stronger reliance on socially endorsed norms acquired through education and media. Therefore, observed differences between age, professional, or educational groups may reflect not only genuine variations in attitudes but also diverse levels of life experience, differential sensitivity to the risk of self-incrimination, and varying degrees of trust in the research process. These alternative explanations highlight the need for caution when drawing generalized conclusions and underscore the value of future studies employing methods designed to reduce social desirability bias, including anonymous experimental designs and indirect questioning techniques.

Recent empirical and review work at the intersection of behavioral economics, decision psychology, and corruption research strengthens the theoretical foundation of this study and clarifies its contribution. A growing literature shows that cognitive biases, social norms and context-sensitive incentives can systematically shape corrupt choices beyond classic expected-utility calculations. In particular: behavioral reviews synthesize heuristic and social-preference mechanisms relevant for corruption (Muramatsu, Bianchi, 2021). Lab-in-the-field experiments demonstrate novel ways to measure corrupt opportunities and reveal how institutional context and incentive structures change willingness to engage in bribery (Armand et al., 2023). Cross-national analyses link monetary aspiration, pay dissatisfaction and risk perceptions to corrupt tendencies across diverse institutional settings. Systematic reviews from psychology identify validated tests and experimental paradigms for assessing corrupt behavior and moral resilience, which can inform instrument design and interpretation. Finally, recent work on messaging and norm-based interventions shows that perceived prevalence of corruption and the framing of anti-corruption messages strongly influence individuals’ propensity to bribe or report corruption (Incio, Seifert, 2024). Together, these studies justify (1) the behavioural framing adopted here, (2) the use of mixed methods and scenario-based survey items, and (3) the interpretation of results through prospect-theory concepts such as loss aversion, reference points and narrow framing.

Hypothesis. Although there is a difference in attitude towards corruption depending on people’s age, education, occupation and their personal economic status, we suppose that people holding degrees, advanced in their career and well-paid still accept corruption as tolerable phenomenon and tend to be corrupted.

Research Question 1: Why do people risk their own well-being by becoming corrupt or allowing themselves to be corrupted? As there is insufficient data on the matter particularly in relation to the Russian Federation, answering this question will help discover the source and psychological roots of corruption. This will be of immense benefit, because it gives understanding to the extent of adaptation and an indicator to ‘red flags’ concerning corruption matters in developing countries, particularly in the Russian Federation (Goldman, 2005). From a behavioral economics point of view the question is closely related to loss aversion and/ or risk seeking behavior within the framework of “subjective expected utility” and good morals (Kobis, 2021).

Research Question 2: Can the understanding of the corruption behavioral origins contribute to the anti-corruption strategies? Answering this research question, we found it helpful to identify how different social groups perceptions of corruption relations varies. It is also crucial in understanding why people are not satisfied with their stability and achieved status.

Methodology and Methods. Besides the empirical study, this study is based on inductive logic and aims to understand the degree of corruption perception of a particular person. In this research process, the mixed methods approach was adopted. Such approach enables the qualitative researcher to create quantitative measures from their qualitative data (Hesse-Biber, 2010).

The following general scientific methods represent the methodological ground of the present article: analysis, synthesis, abstraction, and generalization. The research also uses a number of particular scientific methods: historical-legal, system-functional, formal logical, and statistical. The present research uses sectoral legal methods, such as formal legal method, complex method and doctrinal comparative legal method (Inozemtsev, Nektov, 2023). The materials of the Russian and foreign law enforcement practice in the field of corruption represent the empirical basis of the current study.

In order to answer the research questions, this study relies on the results of a survey conducted among high-earning employees and senior managers in both the public and private sectors. Semi-structured interviews and participants’ observations provide an opportunity for the researcher to deepen the study of a new phenomenon in a way that can determine the causal factors of the phenomenon. This research primarily uses semi-structured interviews to collect data from employees (Huang, 2018). This method is highly suitable for this type of research because it does not require long interviews when employees do not have much time. The Moscow State University for International Relations and its School of Business and International Proficiency students and professors were selected for providing the database, 256 respondents were interviewed.

The survey method adopted in this study was carried out among School of Business and International Proficiency students aged 23 and above. Of the 200 questionnaire sheets distributed, a total number of 198 participants fully completed the questionnaire. Consequently, the result from the respondents represented the upper layer of the population as the whole. The survey questionnaires were not only citizens of the Russian Federation. One person holds Turkish citizenship and lives in Turkey. Two persons are citizens of Azerbaijan. One person has a Russian citizenship, but constantly lives in Hong Kong. Both individuals are originally from Armenia and hold Armenian citizenship, although they have been living in Moscow for a long time. Russian Federation was also presented by different regions: Moscow, Arkhangelsk Region, Dagestan Republic, Bashkiria Republic, Volgograd Region, Stavropol Region, Moscow Region, St. Petersburg, etc.

The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first one included demographic backgrounds of education, age, and profession. The age category was divided into two variables: youth (23-35) and middle age (36-55). 94 persons belong to the youth group and 106 persons belong to middle age group. The profession variable had two categories: public sector and private sector. 80 persons work in public sector and 120 persons work in private sector or are owners of private business. The education variable was divided into ‘higher education’ and ‘scientific degree’. 173 persons belong to ‘higher education’ group and 27 persons have scientific degree – Doctor or Candidate of Science. The second section consisted of thirty-two questions based on three responses (agree, neutral, and disagree). These questions were designed to analyze the perception of respondents regarding corruption. Initially only 8 questions were designed. However, with the progress of analyzing the situation in the Russian Federation the author realized the necessity of broadening the range of questions. An independent sample t-test has been used to analyze the problem.

For the purposes of statistical analysis, all qualitative responses were converted into numerical indicators using a unified coding scheme. Closed-ended questions based on Likert-type scales (e.g., levels of agreement or perceived acceptability of certain behaviors) were assigned numerical values from 1 to 5, where lower values indicated weaker acceptance or lower agreement, and higher values reflected stronger acceptance or higher agreement. Categorical variables such as age group, type of employment, and education level were coded as dummy variables, allowing their inclusion in comparative and correlation analyses. Open-ended responses were processed through thematic coding: each identified theme or behaviorally relevant pattern was assigned a numerical code, after which the frequency of coded categories was quantified. This transformation ensured consistency and comparability across the dataset, allowing the use of descriptive statistics and non-parametric tests to identify behavioral differences between respondent groups.

Research Results and Discussion. The research was conducted among the persons representing the upper layer of society: successful owners of middle-scale business, university professors and high administrative staff, top managers of large corporations. Notwithstanding this fact the research shows that only 18.1% of respondents find their level of income convenient. Though the figure of 65.6% of neutral respondents may show their reluctance to identify their own prosperity. The result of Question 16 is of interest – it shows that the respondents assess their welfare higher than average in the Russian Federation. Here 63.1% of respondents marked ‘agree’ plus 27.8% gave ‘neutral’ answers. The result is quite comparable with the result of Question 1, though vice versa ‘agree’ to ‘neutral’.

At the same time, these results may show that the majority of respondents understand that their economic level is higher than average in the Russian Federation, but they still do not find it convenient. It shows both discontent of their own income level and the general income level in the Russian Federation. Hence, the respondents understand that their life standard is better than the average life standard in the Russian Federation, but still that level does not give them enough freedom and independence they want. The result of the survey shows that the respondents are not satisfied with the level of life in Russia in general and indicates anchoring to international welfare standards within the prospect theory framework. They compare it to the average welfare in the world (Question 17) and provide only 11.1% of answers ‘agree’. At this stage, respondents do not consider countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Uganda or Tajikistan; rather, they consider the world's richest countries: Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland, Ireland, the USA and Australia. This approach highlights the subjectivity of narrow framing when assessing their own economic situation. People cannot be objective when speaking about themselves.

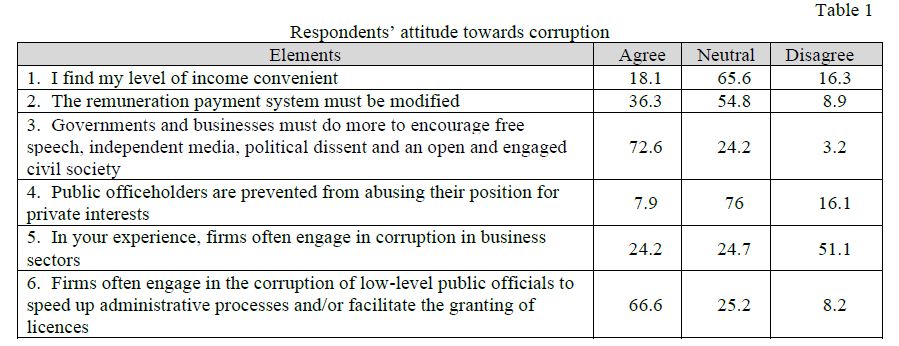

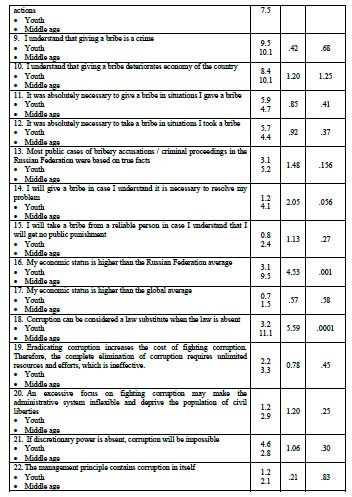

Table 1 shows that 66.6% of respondents agree that firms involve low-level public officials in corruption (75.3% agree). Transparency is recognised as a means of reducing opportunities for state officials to be corrupt (94.2% agree) and as being crucial to the election process (92.5% agree).

The survey indicates that most respondents deal with ‘white’ sectors of economy as 51.1% ‘disagree’ with Question 5 suggesting that in the business sector the respondents having relationship with corporations are often engaged in corruption. Under different corruption reports concerning the Russian Federation (Word Bank & IFC: Doing Business 2022, World Economic Forum: Global Competitiveness Report, 2023, World Economic Forum: Global Enabling Trade Report 2016, Bertelsmann Foundation: Transformation Index – Russia 2022, Freedom House: Nations in Trust – Russia 2022, US Department of State: Investment Climate Statement – Russia 2022, etc.), the sectors of the economy, which are most corrupted are the following: judicial system, public services, police, land administration, customs administration, tax administration, natural resources, public procurement. Half of the respondents work in the mentioned sectors of the Russian economic system, but not all of them agree with the corruption in these sectors. The survey shows that the majority of the respondents were not personally engaged in corruption (52,4% ‘disagree’). Hence it is logical that they deny corruption in the sector in which they work.

The research shows that the respondents understand the fact that giving a bribe is a crime (97.6% ‘agree’) and that giving a bribe deteriorates economy of the country (91.7% ‘agree’). At the same time, 77.6% of respondents recognize it as a routine practice in case of absence of law. These controversies show inconsistency in the way of thinking and actions of the respondents. On the one hand, they are loyal citizens who understand and respect the law; on the other hand, they recognise the reality of current corruption practices. Of those involved in the bribery process, only half of the respondents acknowledge that it was absolutely necessary to give or take a bribe (51.3% and 50.3% respectively). Therefore, although they acknowledge that there was an alternative to bribery, they still participated in the process due to the widespread acceptance of bribery in their minds as well as in business practices.

Less than half of the respondents (46.1%) agree that most cases of bribery accusations in the Russian Federation were based on true facts. The survey therefore shows a lack of trust in the prosecution and judicial systems (Cenerelli, 2020).

The survey shows that, from the outset, it is necessary to promote individuals who are intolerant of corruption. However, supervision is still necessary in 80.4% of cases. Different tests during the recruitment process could be helpful here. A lie detector test can only be used with the candidate's consent. If a candidate does not agree to take a lie detector test, they will not be employed. Experts try to predict whether a candidate for a state office will accept bribes. The lie detector is helpful, though it is not a panacea. Moreover, a person can calmly discuss an abstract situation. However, they cannot predict how they would behave in a particular practical situation. It is also necessary to check a person's biography to see if they are

a friend or relative of an interested person, or a former employee of a company participating in the state procurement process. Candidates with negative experience of corruption will be certified as having passed a practical corruption exam successfully.

The survey indicates correlation in state sector salaries increases and corruption decreases. It promotes the necessity to increase salaries in the state sector to decrease corruption. Although 40.6% show that it is not the only means to fight corruption. Generally, the respondents do not recognize that discretionary power promotes corruption (36,7%) or that any legal norm limiting rights of citizens stimulates corruption (50,9%).

Unfortunately, the research confirms that anti-corruption campaigns in the Russian Federation are ineffective (only 0.8% of respondents think they are effective) and that the fight against corruption requires constant effort. At the same time, respondents are not personally eager to fight corruption, showing much more neutrality in this regard (51.4%). The survey shows that people are not very willing to report a case of corruption of which they become aware (19.6%). The reasons why people in the Russian Federation do not report corruption cases are as follows:

- they think it is dangerous indicating loss aversion,

- they think it’s of no use indicating likelihood insensitivity,

- they do not believe in the possibility to prove something, or

- they do not want to recognize their involvement in corruption practice.

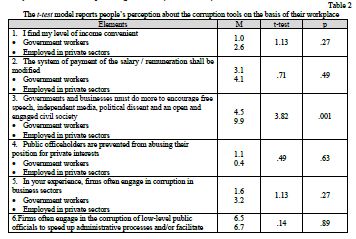

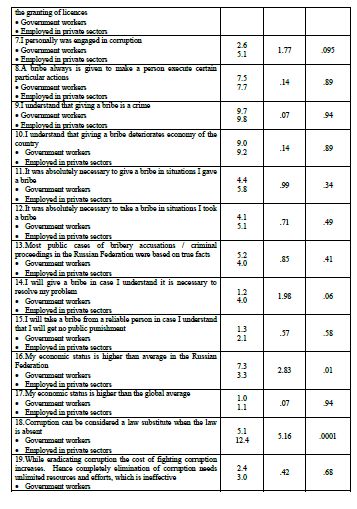

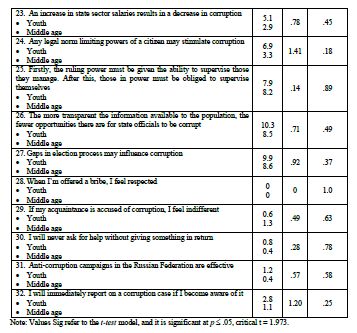

In the part of the survey examining employees in government and private sectors with different professions Table 2 provides evidence that some of the elements presented as criteria of research are true and professional differences were statistically significant when the government sector or the government-related sector was involved: ‘governments and businesses must do more to encourage free speech, independent media, political dissent and an open and engaged civil society’ at the p = .001 level; in assessing the person’s welfare as higher than average in the Russian Federation at the p = .012 level; in understanding corruption as a law substitute when the law is absent at the p = .0001 level; ‘first of all, it is necessary to provide the ruling power with the ability to supervise the managed but after this it is necessary to oblige those who rule to supervise themselves’ at the p = .016; in understanding transparent information as a means for decreasing opportunities for corruption by state officials at the p = .018 level; in considering holes in the election process as influencing corruption at the p = .32 level. Question 18 concerning understanding corruption as a law substitute in case of absence of law showed the highest variation in perception of government employees and employees from private sector.

This means that the respondents whether employees in public or private sectors equally believe that the system of salary payment shall be modified (p = .49), corruption is often used within the area of low-level public officials to speed up administrative processes and/or facilitate the granting of licenses (p = .89), a bribe is always given to make a person execute certain particular actions (p = .89), they will give a bribe in case they understand it is necessary to resolve a particular problem (p = .064) and any legal norm limiting powers of a citizen may stimulate corruption (p = .12). Surprisingly, the survey suggests that both public and private employees believe in the same way that most public cases of bribery accusations / criminal proceedings in the Russian Federation were based on true facts (p = .41) as well as equally understand the concept of absolute necessity in giving a bribe and taking a bribe (p = .34 and p = .49correspondently).

Still insignificant variation proves Question 32 concerning immediately reporting on a corruption in case of awareness of it, though it is close to critical (t = 1.84,

p = .84).

Table 2 shows that when government employees consider questions related to government service their answers vary from answers of private sector employees (Pond, 2018). At the same time in case of indifferent for them questions the answers are similar. This proves that employees with different professions have varying perception of corruption relations when assessing particular economic sector which is sensitive for them (Golesorkhi et al, 2019; Kasyanov & Kriger, 2020).

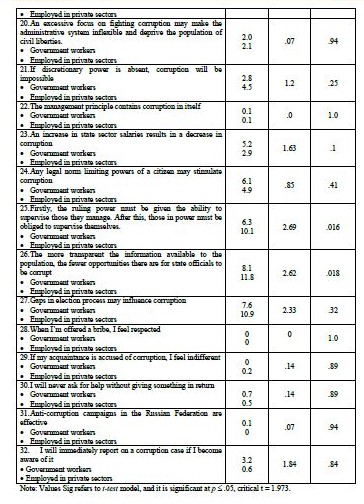

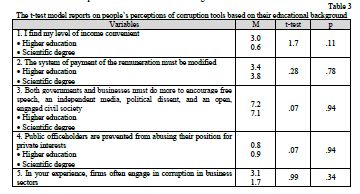

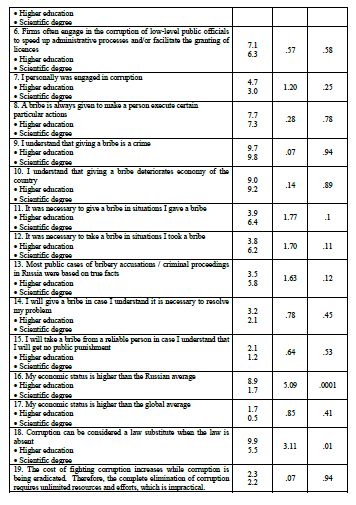

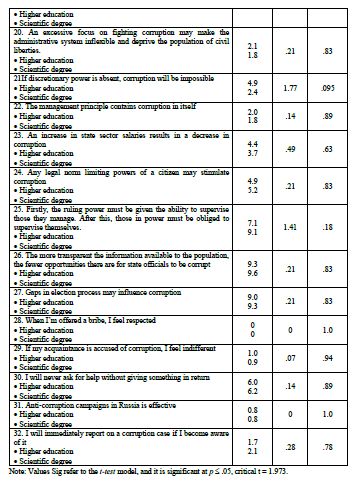

In the section of the survey that examined people’s educational backgrounds and their perceptions of corruption, Table 3 shows that people with a high level of education and those with a scientific degree had a very similar understanding of the relations and influence of corruption on the country’s economy and legal system. Only in two cases Table 3 shows critical differences: in assessing the economic state comparing to the average economic state in Russia (t = 5.09, p = .0001) and in considering corruption as a law substitute (t = 3.11, p = .063).

The result shows that people having scientific degree are highly unsatisfied with their economic level even in comparison with the average level in Russia. In reality it is not true. Of course, people having a scientific degree are paid more than average in Russia and hence, their economic state is higher than average in the Russian Federation. Most probable that the respondents spent such high efforts to achieve their scientific degree, that they want to get not only moral, but material satisfaction from such efforts as well. Those with higher education are more realistic: they don't expect to earn above-average wages and they understand that their economic level is above average in the Russian Federation.

Table 3 shows a drastic difference in the consideration of corruption as a substitute for the law when the law is absent. Respondents with higher education mostly agree with it, but only a small proportion of respondents with a scientific degree agree. This indicates a more antagonistic attitude towards corruption among scientists. Those who research more understand the disastrous consequences of corruption better. When the law is absent, common sense, rather than corruption, should prevail (Kasatkin et al., 2019; Kuteleva et al., 2023; Shashkova & Solovtsov, 2022; Sharipova, 2023).

Higher variations are detected in questions similar to the above. A similar variation to that seen in Question 16, which concerns the assessment of a person's economic state, is evident in Question 1, which asks about the level of income deemed acceptable (t = 1.7, p = .108). Questions concerning the absolute necessity to give or take a bribe (t = 1.77, p = .095), basing bribery accusations in the Russian Federation on true facts (t = 1.63, p = .122), and the impossibility of corruption in the absence of discretionary power (t = 1.77, p = .095) also show variation.

The survey shows that people with a scientific degree have higher expectations for their economic state and are more implacable towards corruption than respondents with higher education.

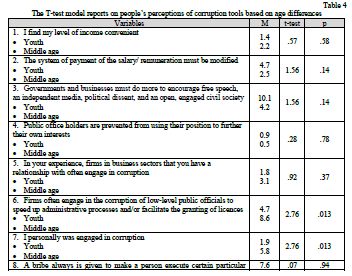

Another section of the survey focuses on how people of different ages perceive corruption. As in the second part of the survey, Table 4 shows that there is critical variation concerning Question 16, which relates to the assessment of the economic state (t = 4.53, p = .001), and Question 18, which relates to understanding corruption as a substitute for the law if the law is absent (t = 5.59, p = .0001). This can be interpreted as a similar approach to corruption relations by distinct groups. Surprisingly, the perception of young people can be compared with the perception of people with a scientific degree rather than people with higher education. People with a scientific background automatically use deeper analytical skills to assess corruption and corrupt behaviour. Young people have a similar understanding of these phenomena, showing intuition, an open mind, and a better grasp of reality than middle-aged people. Comparing these results with those in Table 2, it can be concluded that the results for Questions 16 and 18 are similar for business owners and people employed in the private sector. The private sector is always more flexible than the government sector, which makes it understandable why private sector employees gave answers similar to those of the young people. Therefore, scientists' perception of corruption is similar to that of the agile private sector and youth. In summary, analytical skills produce similar results to those produced by agility and an open mind.

In this case, salary matters (t = 1.56, p = .138), the idea of political independence (t = 1.56, p = .138), the basing of bribery accusations on true facts (t = 1.48, p = .156), and the understanding of any legal norm that limits the powers of a citizen as stimulation for corruption (t = 1.41, p = .175) are also marginal. Therefore, Table 4 shows that people of different ages have different understandings of the tools of corruption.

Conclusion. The findings of this study provide new insights into the origins of corruption, which cause people to jeopardise their stability. The survey shows that well-paid employees tend to regard corruption as routine and are more likely to engage in activities that could be considered corrupt than to refrain from doing so. The legal framework and liability have little impact on decision-making. Respondents may consider their income level to be higher than average in Russia, yet still be willing to engage in corruption as a routine phenomenon.

The stratification of society (social, economic, political, etc.) has an impact on the reasons for corruption. Although education level could seem relevant to different attitudes towards corruption, the survey shows that even highly educated people still consider corruption tolerable. Only a scientific degree increases intolerance of corruption, albeit not significantly. This may be a particular feature of Russia, where higher education is widely accessible.

The survey shows that corruption is widely accepted as a natural and traditional fact of life. Only a few people believe that corruption in the public sector is curbed by legal provisions, with no place for private interests (see Table I). The majority believes that corruption in the public sector, especially in the Russian Federation, is inherent at all levels and in all sectors.

Well-paid top managers decide to engage in corruption, or to accept it, mostly due to the general tolerance of corruption. At the same time, they would rather play a passive role and not challenge traditions and routine corrupt practices.

The public appreciates anti-corruption measures that are effective rather than just declarative. This approach was evident in the survey responses. There is a need to rely on the state system as a fair and effective supervisor. People do not view corruption counteraction as their personal responsibility, and are not willing to jeopardise their career or remuneration for anti-corruption measures. These findings on the behavioural origins of corruption among well-paid employees are relevant to both the private and public sectors.

Reference lists

Armand, A., Coutts, A., Vicente, P. C., & Vilela, I. (2023), “Measuring corruption in the field using behavioral games”, Journal of Public Economics, 218, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2022.104799.

Barberis, N. (2013), “Thirty Years of Prospect Theory in Economics: A Review and Assessment”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27 (1), 173-96, DOI 10.3386/w18621.

Bruhin, A., Fehr-Duda, H. & Epper, Th. (2010), “Risk and Rationality: Uncovering Heterogeneity in Probability Distortion”, Econometrica, 78, 1375-1412, DOI:10.2139/ssrn.1415975.

Cenerelli, A. (2019), “Administrative justice in Russia”, Diritto pubblico comparato ed europeo. Rivista trimestrale, (1), 101-136, DOI:10.17394/92977.

Dupuy, K. & Neset, S. (2018), The cognitive psychology of corruption: Micro-level explanations for unethical behavior, Working Paper Anti-Corruption Resource Center.

Gans Morse, J., Kalgin, A., Klimenko, A., Vorobyev, D., Yakovlev, A. (2021), “Self Selection into Public Service When Corruption is Widespread: The Anomalous Russian Case”, Comparative Political Studies, 54(6), 1086-1128, DOI: 10.1177/0010414020957669.

Goldman, M. (2005), “Political Graft: The Russian Way”, Current History, October,313-318, DOI: 10.1525/curh.2005.104.684.313.

Golesorkhi, S., Mersland, R., Randoy, T., & Shenkar, O. (2019), “The Performance Impact of Culture and Formal Institutional Differences in Cross-Border Alliances: The Case of the Microfinance Industry”, International Business Review, 28 (1), 104-118, DOI: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.08.006.

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2010), Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice, New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Heywood, P. (2017), “Rethinking Corruption: Hocus-pocus, Locus and Focus”, Slavonic and East European review, 95 (1), 21-48, DOI:10.5699/slaveasteurorev2.95.1.0021.

Huang, W.-Y. (2018), “Influence of Transparency on Employees’ Ethical Judgments: A Case of Russia”, Journal of Business Ethics, 152 (4), 1177-1189, DOI:10.1007/s10551-016-3327-z.

Incio, J., Seifert, M. (2024), “How the Perception of Corruption Shapes the Willingness to Bribe: Evidence From An Online Experiment”, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 36(3), DOI: 10.1093/ijpor/edae035.

Inozemtsev, M. I., Nektov, A. V. (2023), “Foreign Dissertations on Digital Law: Statistical and Literature Review”, Digital law Journal, (4), 1, DOI: https://doi.org/10.38044/2686-9136-2023-4-1-28-63.

Kasatkin, P. L., Kovalchuk, J. A., & Stepanov, I. M. (2019), “The modern universities role in the formation of the digital wave of Kondratiev’s long cycles”, Voprosy Ekonomiki, (12), 123-140, DOI: 10.32609/0042-8736-2019-12-123-140.

Kahneman, D. (2003), “Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics”, American Economic Review, 93 (5), 1449-1475, DOI: 10.1257/000282803322655392.

Kasyanov, R., Kriger, A. (2020), “Towards Single Market in Financial Services: Highlights of the EU and the EAEU Financial Markets Regulation”, Russian Law Journal, 8(1), 111-137, DOI: 10.17589/2309-8678-2020-8-1-111-137.

Kobis, N. C., Bonnefon, J.-F., & Rahwan, I. (2021), “Bad machine corrupt good morals”, Nature Human Behaviour, 5 (6), 679-685, DOI:10.1038/s41562-021-01128-2.

Kuteleva, M.A., Ganevich, O.K., Romel, S.A. (2023), “Bribery as a Form of Corruption”, International Journal of Professional Science, (1), 5-10.

Muramatsu, R., Bianchi, A. (2021), “Behavioral economics of corruption and its implications”, Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 41(1), 100-116, DOI: 10.1590/0101-31572021-3104, EDN: JOJLUC.

Povetkina, N.A., Ledneva, Yu.V., & Veremeeva, O.V. (2020), “Women in public finance of Russia and the world”, Woman in Russian Society, (4), 66-81, DOI: 10.21064/WinRS.2020.4.6.

Pond, A. (2018), “Protecting Property: The Politics of Redistribution, Expropriation, and Market Openness”, Economics and Politics, 30 (2), 181-210, DOI: 10.1111/ecpo.12106.

Rose-Ackerman, S., & Palifka, B. (2016), Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences and Reform, 2nd Edition, Cambridge University Press, DOI:10.1111/gove.12273.

Sharipova, O. O. (2023), “Corruption Is the Bane of National Development NovaInfo”, Ru, (135), 158-159.

Shashkova, A. V., Solovtsov, A. O. (2022), “Factors of Development and Success of Digital Platforms”, The Platform Economy: Designing a Supranational Legal Framework, 19-35.

Smith, V. (2003), “Constructivist and Ecological Rationality in Economics”, American Economic Review, 93 (3), 465-508, DOI: 10.1257/000282803322156954.

Thaler, R. (2016), “Behavioral Economics: Past, Present, and Future”, American Economic Review, 106 (7), 1577-1600, DOI: 10.1257/aer.106.7.1577.

Wakker, P. (2010), Prospect Theory for Risk and Ambiguity, Cambridge University Press, DOI:10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.002.

Winter, H. (2017), Issues in Law and Economics, The University of Chicago Press.

Wright, J. & Ginsburg, D. (2012), “Behavioral Law and Economics: Its Origin, Fatal Flaws and Implications for Liberty”, Northwestern University Law Review, 106, 1033-1088, DOI:10.4324/9781315730882-15.

Zaloznaya, M. (2017), “The Social Psychology of Corruption: Why it does not exist and why it should”, Sociology Compass, 8(2), 187-202, DOI:10.1111/SOC4.12120.