Новые логические основания исследования православной воцерковлённости

Aннотация

Среди социологов религии есть мнение о том, что невозможно квантифицировать религиозность методом опроса. Автор отвергнул крайность один из вариантов такой методики. Известная социолог – исследовательница православия В. Ф. Чеснокова создала индекс воцерковлённости (В-индекс), распределяющий респондентов по пяти группам воцерковлённости в соответствии

с наиболее сильным ответом на пять основных вопросов о фактической религиозности. Дополнительные вопросы могли изменить результат только в сторону усиления воцерковлённости. Предыдущие критические статьи о В-индексе доказали его некорректность. Настало время предпринять попытку исправить этот инструментарий. Во избежание завышения численности глубоко верующих предложено перестроить логические основания вышеупомянутой методики измерения степени православной религиозности. Вместо чёткой принадлежности к одной из пяти групп в соответствии с фактической религиозностью предложена нечёткая принадлежность к единой группе православных на основе сопоставления фактической религиозности с нормативной. Рассмотрены разные варианты функции принадлежности. Разработаны требования к данному элементу социологической методики: она должна, во-первых, быть математически корректной, во-вторых, реализовывать следующее положение: чем ближе друг к другу аргументы функции (т.е. чем более соответствуют друг другу конкретная х и абстрактная у модальности), тем больше значение функции, чем дальше - тем меньше. По всем критериям применяется функция принадлежности вида 𝜇𝐴(𝑎) = 1 − |𝑥 − 𝑦|. Глубокая модернизация подхода к эмпирической квантификации степени православной религиозности позволила создать инновационный инструментарий измерения количества верующих.

Ключевые слова: религиозность, степень православной религиозности, квантификация признака, индекс воцерковлённости, нечёткая логика, деонтическая логика, морфологический подход к измерению религиозности

К сожалению, текст статьи доступен только на Английском

Introduction (Введение). In recent years, the mathematical modeling of social groups has been developed (Eshghi, Williams, 2017a), (Eshghi, Williams, 2017b), (Whitaker, Turner, Colombo, 2018). The specificity of social groups of the Orthodox type also receives some attention (Divisenko, 2016), (Mankoff, Miller, 2018). Some sociologists believe that religiosity is either not quantifiable at all, or very difficult (Markin, 2018). This opinion is widespread both among theorists and among practitioners, for example, those involved in state-confessional relations (Basil, 2005).

On the one hand, some authors researching religiousness in society, displace an accent from state-religious to secular-religious interaction (Kotelnikov, Lebedev, 2004), (Lebedev, 2007), (Reutov, 2008). It may be justified in current political situation characterised by declared secularity of the state. But in case of change the secular character of the state constructed theoretical model of state-religion interaction will not lose heuristic potential (whereas secular-religious one will cease to be representative), i.e. is more universal. On the other hand, nondichotomous relation between state and religious sides makes a ground for conflict: for example, believing official, that decides to transfer a religious-purposed object from state property to property of religious organisation. If he/ she knows, that it is illegal, but his/ her bishop (mufti, rabbi, pastor, lama etc.) blesses such transfer, then what norms will be carried out: state or religious? Guided by classical logic, it is impossible to answer this question, since the person in question belongs to both social groups at once. To answer this question, fuzzy logic is needed, it allows an element to belong to the set not binary {0; 1}, but with some degree of membership from the interval [0; 1].

Methodology and methods (Методологияиметоды). Examination of the possibility of measuring religiosity. But first it is necessary to consider the possibility of measuring religiosity. Fuzzy logic allows you to do this, but there are also doubters. For example, D. A. Uzlaner writes: «The question arises: on what basis is a person who believes in God but does not attend a church is considered less religious than one who goes to church? The answer to this question is obvious for a theologian based on a certain tradition, but not for a sociologist» (Uzlaner, 2008: 64). But the right question is given the wrong answer: «Consequently, the sociological interpretation of secularization, while remaining within the limits of scientificity, cannot deal with the problem of religiosity as such» (Uzlaner, 2008: 64). This does not fit with the analysis of secularization at the micro level, about which, along with the macro and meso levels, the author writes. The explanation for this discrepancy is as follows: «At the micro level, the study of secularization implies an analysis of the influence of religious ideas and religious consciousness. It's not about how religious certain individuals are, but whether their religiosity influences behavior, such as how people vote or pay taxes» (Uzlaner, 2008: 65). If you do not investigate how religious an individual is, then the sociologist has access to data on religiosity only on a nominal scale, whereas electoral or tax activity can have at least an interval character according to the electoral and economic cycles. For comparison with data on religiosity, a nominal scale will have to be used – to limit voting and payment of taxes by the fact of performing this action. But then the sociologist deliberately impoverishes his research capabilities and, moreover, perhaps reflects social reality inadequately: it is clear that a person who voted in elections only once and a person who regularly participates in them exhibit significantly different social activity, but the nominal scale obscures this.

Nevertheless, D. A. Uzlaner insists: «…to name the transformation of religiosity as secularization, it is necessary to define what is considered a religious norm, which, as shown above, is difficult if we do not take theological positions» (Uzlaner, 2008: 64). In fact, there is no difficulty – you just need not to absolutize this or that religious tradition, not to ask the same questions to respondents, regardless of their confessional self-identification. I.e. before the question about attending a church (and, therefore, before making a decision about the depth of the respondent's religiosity), it is necessary to ask the question of what tradition the respondent considers himself to. If the religion, the identity with which the respondent declares, has a requirement to attend church, but the respondent does not fulfill it, then he is less religious than the respondent who does not attend church, in whose tradition there is no requirement to attend church.

Thus, the answer to the question «What is considered a religious norm?» must be given by the respondent, not the sociologist. The researcher should only foresee in advance the possible variants of different attitudes towards religion. This removes the contradiction between sociology and theology. Of course, the sociologist must know what requirements are imposed on believers by their religion, and he can ask if the respondent fulfills these requirements – but only the respondent who declared belonging to this religion.

We completely reject the position of D. A. Uzlaner, regarding it as a deviation into agnosticism, which arose as a result of the search for universal sociological criteria of religiosity on theological grounds. Of course, to formulate specific questions of the questionnaire, one should use theological material, but not one religion, but all those whose confessions can be expected from the respondent. Thus, it is advisable to join the majority of both Russian and foreign scientists who believe that the measurement of religiosity is not only possible, but also necessary.

Association of deontic logic and morphological approach. To describe and analyze this situation, we need not only fuzzy logic, but also modal, and specifically – deontic. It is on the basis of comparing the norms of the tradition, to which the respondent considers himself, and how these traditions are fulfilled by the respondent, that one can draw a conclusion about the degree of his/ her religiosity. Let us introduce two concepts, respectively: abstract modality and concrete modality. They relate to each other as de jure and de facto: on the one hand, the normative requirements for the believer, enshrined in religious doctrine, on the other hand, the degree to which the believer fulfills these requirements. Contents for abstract modality is taken from the religious texts (specifically for each tradition, so every believer should be asked for only his/ her tradition), for concrete one – from empirical survey.

Logicians have created a strong method for describing and analysing the sphere of duty: «The normative status of an action is expressed in terms such as “permitted”, “prohibited”, “obligatory”, “normatively indifferent”, “should”, “should not”, “may”, “necessary”, etc.» (Nonclassic…, 2006: 33). However, in this list there is no single system, the concepts intersect and enter into each other, there are not only deontic, but also aletic modalities, and the list is open. In addition, if we want to compare Orthodox and Islam, like it did J. J. Sinelina (Sinelina, 2009, 2013), it will be impossible with such method, since in this religion, along with the indifferent (mubah), obligatory (fard) and prohibited (haram), the permitted (halal) is divided into desirable (wajib), neutral (i.e., the aforementioned indifferent “mubah”) and undesirable (makruh). All this means that it is impossible to use the above list of deontic modalities unchanged in our study.

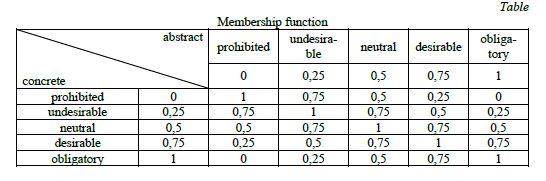

Research Results and Discussion (Научныерезультатыидисуссия). The author’s position is that, using the morphological approach, two parameters should be distinguished: the nature of the norm that regulates the action, and the assessment given to the action by the rule-maker. The norm can be dispositive or imperative, and the assessment can be positive or negative. Thus, we obtain four combinations, each of which can be assigned a degree of belonging: imperative-positive “obligatory” (1), dispositive-positive is “desirable” (0.75), dispositive-negative is “undesirable” (0.25), imperative negative is “prohibited” (0).

The beginning of the scale from zero does not mean that this scale is absolute – on the contrary, in fact, it is a rank scale (Paniotto, Maximenko, 1982: 14). Thus, it cannot be said that a desirable action gives a person 25% less religious affiliation than an obligatory one, or that from a religious point of view, a desirable action is three times better than an undesirable one. But we can say that undesirable is better than prohibited etc.

In addition, the absence of negative values in the scale does not mean that there are no negative values at all. The role of negative values is played by negative assessments of actions given by the rulemaker. I.e. negative values are “dispositive-negative” (0.25) and “imperative-negative” (0). «If the rank scale provides for both positive and negative assessments, then its positions are arranged symmetrically: the number of positions with a positive value is equal to the number of positions with a negative value, and between them there is a position with a neutral (zero) value» (Gorshkov, Sheregi, 2001: 65). Therefore, a value of 0.5 can be assigned to the neutral action. Neutral point is need to reflect the situations that, on the one hand, don’t have a religious regulation or this regulation is ambiguous, on the other hand, are important in the design of the survey. Its interpretation depends on research tasks, for example, if the task is to typologize respondents, then neutral point can be an analogue for respondents who hesitate between faith and atheism.

Construction of fuzzy membership functions. The respondent's modality of the norm can be either weaker, or the same, or stronger than that established by the norm itself. It seems quite natural to assume that the degree of belonging to a group directly depends on this attitude, i.e.  , where m - a membership function, А - social group, а - respondent, х - concrete modality, у - abstract modality. At first glance, the economic method of calculating efficiency as a ratio of fact to plan can be used in religious studies. However, such function cannot be used either from a formal or substantive point of view.

, where m - a membership function, А - social group, а - respondent, х - concrete modality, у - abstract modality. At first glance, the economic method of calculating efficiency as a ratio of fact to plan can be used in religious studies. However, such function cannot be used either from a formal or substantive point of view.

On the formal side, the impossibility of applying the aforementioned membership function lies in the difficulties with the analysis of the observance of prohibitions and, more generally, in the logical inconsistency. The abstract modality “prohibited” has a value of zero, which is not allowed in the denominator of the fraction. And without attention to prohibitions, the study will be deliberately incomplete. But even if we cross out the zero value from the scale, then at  and

and  it turns out

it turns out  , i.e. the value of the function is off scale - this move is inadmissible.

, i.e. the value of the function is off scale - this move is inadmissible.

On the substantive side, the problem is that respondents who most accurately fulfill their socio-group norms (i.e., when a specific modality of a norm is identical to an abstract one) will turn out to be less belonging to the group than fanatics who adhere to a stronger modality. This assumption makes it impossible to study Christianity and Judaism, since the scripture repeatedly prohibits liberty in dealing with the prescribed rules. For example: «Ye shall observe to do therefore as the LORD your God hath commanded you: ye shall not turn aside to the right hand or to the left» (Deut. 5: 32), «…to keep and to do all that is written in the book of the law of Moses, that ye turn not aside therefrom to the right hand or to the left» (Josh. 23: 6), «Turn not to the right hand nor to the left…» (Prov. 4: 27). In our terms it means the condition  .

.

A slightly more complex situation with Christianity. On the one hand, the above quotes are not only part of the Old Testament of the Bible, but are also confirmed in the New Testament by Christ himself: «Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfil. For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled» (Mt. 5: 17-18). I.e. believers are still required to fulfill the condition  . On the other hand, it is not the simple implementation of the law that is important, but even more enhanced: «…That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven» (Mt. 5: 20). I.e. the condition of salvation changes significantly:

. On the other hand, it is not the simple implementation of the law that is important, but even more enhanced: «…That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven» (Mt. 5: 20). I.e. the condition of salvation changes significantly:  . But in this case, firstly, the aforementioned formal obstacles with zero value and off-scale remain, and secondly, in practice, deviations from the norm, including exceeding the proper value of the parameter, are not always useful.

. But in this case, firstly, the aforementioned formal obstacles with zero value and off-scale remain, and secondly, in practice, deviations from the norm, including exceeding the proper value of the parameter, are not always useful.

If we try to model the superiority of personal righteousness over the Pharisee as a necessary condition for belonging to Christians without the problem of division by zero, we get the membership function  . The bottom line expresses a righteousness not exceeding (i.e. less than or equal to) the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees. But with the help of this function it becomes impossible to describe the other extreme position of the scale. Both concrete and abstract modalities “obligatory” have a numerical value of 1 (or any other number - it is only important that at the top of the scale, a concrete modality a priori cannot surpass the abstract one). Therefore, the bottom line will always be fulfilled - nobody has an objective opportunity to fulfill the divine command to surpass the righteousness of the Pharisees, i.e. all are doomed to perish. This conclusion contradicts the essence of Christianity and, therefore, turns it into a simulacrum - this move is inadmissible.

. The bottom line expresses a righteousness not exceeding (i.e. less than or equal to) the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees. But with the help of this function it becomes impossible to describe the other extreme position of the scale. Both concrete and abstract modalities “obligatory” have a numerical value of 1 (or any other number - it is only important that at the top of the scale, a concrete modality a priori cannot surpass the abstract one). Therefore, the bottom line will always be fulfilled - nobody has an objective opportunity to fulfill the divine command to surpass the righteousness of the Pharisees, i.e. all are doomed to perish. This conclusion contradicts the essence of Christianity and, therefore, turns it into a simulacrum - this move is inadmissible.

Thus, the membership function we are looking for must satisfy the following requirements: firstly, it must be mathematically correct, and secondly, it must implement the following position: the closer the function arguments are to each other (i.e., the more the concrete x and abstract y modality), the greater the value of the function, the further - the less.

These requirements are met by the function  . All actions associated with this function are feasible for numbers from the range [0; 1], and the value of the function does not go off scale. The modulus of the difference x and y is the degree of remoteness of the concrete and abstract modalities from each other (in other words, the inaccuracy of the respondent fulfilling his/ her social-group norms), and subtracting it from one shows that the more accurately the respondent fulfills the norms of his/ her social group, the more he belongs to it.

. All actions associated with this function are feasible for numbers from the range [0; 1], and the value of the function does not go off scale. The modulus of the difference x and y is the degree of remoteness of the concrete and abstract modalities from each other (in other words, the inaccuracy of the respondent fulfilling his/ her social-group norms), and subtracting it from one shows that the more accurately the respondent fulfills the norms of his/ her social group, the more he belongs to it.

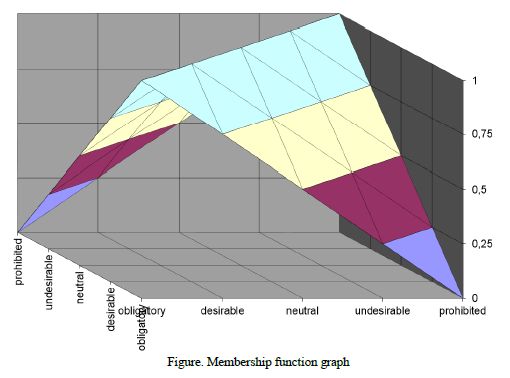

In accordance with our position on the quantification of religiosity, the domain of definition and the range of values of this function are discrete and have a cardinality of five. In order to comprehensively (i.e., not only analytically, but also tabularly and graphically) set the function of belonging to a particular religious tradition, the author carried out the corresponding computational and illustrative procedures (see Table. and Figure).

Observation of churchliness in native and international contexts. Many methods have been developed for studying the religiosity of the population: on the basis of indicators of self-identification, religious consciousness, religious behavior, consciousness and behavior together, as well as the method of expert assessments (Lokosov, Sinelina, 2008). As a rule, a believer is required to recognize his/ her religious affiliation, know sacred texts and dogmas, perform rituals, celebrate religious holidays, etc. Unfortunately, different authors approach the set of operational indicators of religiosity without following any standard. For example, observance of fasts is mentioned only by L. A. Andreeva and L. K. Andreeva, but in the analysis of the data they received, there is no information about fasting (in contrast to the attendance of a church and making prayers) (Andreeva, Andreeva, 2010: 97). Whereas other authors use the post indicator (Barannikov, Matronina, 2004: 131), but don’t pay attention to prayer.

If we pay attention not only to the list of criteria, but also to their due values, then it is necessary to mention the active discussion that was conducted between the supporters of the soft (Sinelina, 2001, 2005, 2006) and hard approaches. The latter proved to be more convincing: «No matter how multifaceted the personal religious experience of the Orthodox, but if he/ she expects in the future life of rebirth, and not the judgment of God, if he/ she cannot express in words faith in the living, suffering, personal God, on whose love his/ her salvation depends, but speaks of influencing him cosmic power, it is difficult to understand what his/ her Orthodoxy consists of» (Filatov, Lunkin, 2005: 41).

Among all the methodological developments, the most complete is the one created by V. F. Chesnokova (Chesnokova, 2005) toolkit - the index of churchliness (or C-index). In one form or another, it combines most of the criteria used by other scholars (probably with the exception of religious holidays). It is so good that one of the three most prestigious and big Russian organisation for sociological research uses it (Churchliness…, 2014). In addition, the C-index is most widespread both in regional and in all-Russian research practice (Alexeeva, 2009), (Bogatova, 2011), (Prutskova, 2012), (Ufimtseva, 2013). We think that FOM and individual researches wouldn’t use this method if it was strongly incorrect, bad, marginal or inappropriate. Thus, it is precisely due to the complexity, on the one hand, and popularity, on the other hand, that this technique can be taken as a basis for research. Despite the fact that this index is in the mainstream of a soft rather than a hard approach (Lebedev, Sukhorukov, 2013), we can take advantage of this development. However, it needs to be adapted to our method of comparing abstract and concrete modalities, because these modalities in the index are in a “fused” state. It is possible that in the future this method can be used to study atheism, agnosticism, and Buddhism (Oppy, 2018), (Lindahl, Fisher, 2017).

We would like to focus on the C-index developed by V. F. Chesnokova, the most famous researcher of the phenomenon of churchliness; it was she who introduced this concept into scientific circulation. Her developments went to the international level: “In the two most thorough analyses of Orthodox religious life in Russia, V. F. Chesnokova has shown that religiosity and churchliness are complex processes that cannot be gauged by any one indicator. Her analysis explored the Orthodox religiosity of Russians using a complex array of indicators…” (Marsh, 2008: 90). C-index is near to other approaches of quantitation in researches of religion (Glock, Stark, 1974). Using the C-index, sociologists can research Orthodox component of bricolage (Hervieu-Léger, 2015), (Yatsutsenko, 2014), (Folieva, 2014), (Trofimov, 2016). In the context of patchwork religion (Wuthnow, 2007) C-index can be used to explore Orthodox patch.

Historically, considering the concept of being churched, one can find that it was introduced into the Russian sociology of religion about twenty-five years ago. The final monograph, in which the results obtained by V.F. Chesnokova, the founder of this methodological tradition, was a book entitled “In a narrow path: the process of churching the population of Russia at the end of the XX century” (Chesnokova, 2005). There is a clear biblical reminiscence in this title: “Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it” (Мt. 7: 13).

The research subject was originally formulated as follows: “The chosen phenomenon of a person's becoming churched, i.e. his/ her, so to speak, ‘habitation’ in the Church – the knowledge of its charter, rituals, customs, in short, - its everyday existence, feeling oneself in this sphere as one's own, - allows one to probe a person's adherence to this religion through his/ her lifestyle” (Chesnokova, 2005: 8). In the future, the concept is detailed by explicitly defining, but not the concept of churchliness, but related:

- “Churching is a person’s voluntary recognition of the influence of the Church through assimilation of the way of life and way of thinking established in it” (Chesnokova, 2005: 18).

- “The churching of a person is his/ her mastering the church way of life, the church way of thinking, church points of view that exist at the moment” (Chesnokova, 2005: 275).

- “The churching of public consciousness is the assimilation by a mass of people who participate in it of the basic concepts related to the religious sphere: the establishment of their exact content, the correct methods of their application, connections and distinctions between them” (Chesnokova, 2005: 275).

V. F. Chesnokova developed an index of churchliness (С-index), consisting of a selection question, five main questions and six additional questions. With the help of this methodology, all respondents with Orthodox self-identification can be ranked according to five groups:

- V - very weakly churched (zero group),

- W - weakly churched,

- B - beginners,

- S - semi-churched,

- C - churched (church people).

So, if a sociologist rewrites the questions in deontic scale, then every group will become a part of fuzzy membership function. That is the way to integrate deontic and fuzzy logics into research of Orthodox religiosity.

Conclusion (Заключение). Article can be resumed in some points. Firstly, religiosity can be quantified by sociological survey; the dissenting authors are wrong. Some scientists claim that sociology imposes the religion tradition by asking questions to respondents who don’t belong to it. We think that there wouldn’t any problem if interviewer used different questions in accordance with the respondents’ denomination. Therefore, sociology can and must find place in empirical and theoretical researches of religion. Secondly, deontic logic, associated with morphological approach, gives the five-level ordinal scale for measurement of religiosity. Morphological approach streamlines the following deontic values: prohibited, undesirable, neutral, desirable, obligatory. This cognitive optic allows to associate two parameters (abstract and concrete modalities) with aforementioned values. Thirdly, fuzzy logic gives the membership function to match respondents and scale. There are some possible ways to evaluate the empirical religiosity by theoretical categories. A part of them have problem features that disturb to use them in calculation of religiosity. We suppose that the best membership function is based on modulus and subtraction. Fourthly, C-index is the one of research methods that has Russian origin and international perspectives in contexts of bricolage and patchwork religion. This method has an interesting history of being developed. In spite of ambivalent experience of applying it in sociological researches, we think that C-index can be reconfigurated by our approach that allows to replace five non-fuzzy groups by one fuzzy group of Orthodox Christians (with different degrees of affiliation) and then to use all the power of fuzzy logic methods for data processing.

Список литературы

Alexeeva, M. S. (2009), “Churchliness as an indicator of religiosity”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (9), 97-102. (In Russian)

Andreeva, L. А. and Andreeva, L. К. (2010), “Religiousness of student youth. The experience of comparing with the religiosity of Russians”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (9), 95-98. (In Russian)

Barannikov, V. P. and Matronina, L. F. (2004), “Dynamics of religiosity in the information society”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (9), 102-107. (In Russian)

Bogatova, O. A. (2011), “Religious identity and religious practice in Mordovia”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (8), 114-122. (In Russian)

Churchliness of Orthodox believers (2014), available at: http://fom.ru/TSennosti/11587 (Accessed 27.07.2020). (In Russian)

Gorshkov, М. К. and Sheregi, F. E. (2011), Applied Sociology: Methodology and Methods, Moscow, Russia, available at: https://www.isras.ru/files/File/Prikl_Soc_full.pdf, IS RAS (Accessed 27.07.2020). (In Russian)

Divisenko, К. S. (2016), “In a narrow way and in the right direction: the problem of identifying a strong group of Orthodox believers”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (10), 128-138. (In Russian)

Kotelnikov, G. А. and Lebedev, S. D. (2004), “Conceptual models of interaction between secular and religious cultures”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (5), 121-125. (In Russian)

Lebedev, S. D. (2007), “The secular school and the reproduction of religiosity in a secular society”, Knowledge. Understanding. Skill, (1), 72-78. (In Russian)

Lebedev, S. D. and Sukhorukov, V. V. (2013), “The narrow path is not there?”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (1), 118-126. (In Russian)

Lokosov, V. V. and Sinelina, J. J. (2008), “Religious state of modern Russian society (sociological aspects)”, available at: http://www.interfax-religion.ru/?act=analysis&div=103 (Accessed 07.08.2019). (In Russian)

Markin, K. V. (2018), “Between belief and unbelief: non-practicing Orthodox Christians in the context of the Russian sociology of religion”, Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, (2), 266-282. (In Russian)

Nonclassical logic: tutorial (2006), compiler Kuparashvili, М. D., ОmSU Press, Omsk, Russia. (In Russian)

Paniotto, V. I. and Maximenko, V. S. (1982), Quantitative Methods in Sociological Research, Naukova dumka, Kiev, USSR. (In Russian)

Prutskova, Е. V. (2012), “Operationalization of the concept of religiosity in empirical research”, State, religion, church in Russia and abroad, (2), 267-293. (In Russian)

Reutov, N. N. (2008), “Sociocultural practices of integrating religious and secular education”, Ph.D. Thesis, Saratov, Russia. (In Russian)

Sinelina, J. J. (2001), “On the criteria for determining the religiosity of the population”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (7), 89-96. (In Russian)

Sinelina, J. J. (2005), “Churchliness and superstitious behavior of residents of the Yaroslavl region”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (3), 96-107. (In Russian)

Sinelina, J. J. (2006), “The dynamics of the process of churching Orthodox”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (11), 89-97. (In Russian)

Sinelina, J. J. (2009), “Orthodox and Muslims: A Comparative Analysis of Religious Behavior and Value Orientations”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (4), 89-95. (In Russian)

Sinelina, J. J. (2013), “On the dynamics of the religiosity of Russians and some methodological problems of its study (religious consciousness and behavior of Orthodox Christians and Muslims)”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (10), 104-115. (In Russian)

Trofimov, S. V. (2016), “Formation of beliefs in modern society as a process of ‘bricolage’”, V All-Russian sociological congress “Sociology and society: social inequality and social justice”, UrFU, Ekaterinburg, Russia, 1225-1227. (In Russian)

Ufimtseva, E. I. (2013), “Specifics of churchling in assessments of Orthodox youth”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (1), 127-135. (In Russian)

Uzlaner, D. А. (2008), “Secularization as a sociological concept (according to research by Western sociologists)”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (8), 62-67. (In Russian)

Filatov, S. B. and Lunkin, R. N. (2005), “Statistics of Russian religiosity: the magic of numbers and ambiguous reality”, Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniia, (6), 35-45. (In Russian)

Folieva, T. A. (2014), “Religious self-socialization of adults as bricolage”, Materials of Four international scientific conference “Sociology of religion in the late Modern society”, Lebedev, S. D. (ed.), Belgorod, Russia, 283-287. (In Russian)

Chesnokova, V. F. (2005), In a narrow path: the process of churching the population of Russia at the end of the XX century, Academic project, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Yatsutsenko, J. V. “An attempt to define contemporary Religious representations and practices: Danièle Hervieu-Léger”, RUDN Herald, series Sociology, (4), 18-32.

Basil, J. D. (2005), “Church-State Relations in Russia: Orthodoxy and Federation Law, 1990-2004”, Religion, State & Society, (2), 151-163.

Glock, C. Y. and Stark, R. (1974), American Piety: the Nature of religious Commitment, University of California Press, London, UK, Berkeley and Los Angeles, USA.

Hervieu-Léger, D. (2015) “In Search of Certainties: The Paradoxes of Religiosity in Societies of High Modernity”, State, religion, church in Russia and abroad, 33 (1), 254-268.

Mankoff, J. and Miller, A. (2018), “Ukraine’s Church Politics in War and Revolution”, in Oliker, O. (ed.) Religion and Violence in Russia, Rowman&Littlefield, Lanham, Boulder, New-York, London, UK, 233-262.

Marsh, C. (2008), “Russian Orthodox Christians and Their Orientation toward Church and State”, in Daniel, W. L., Berger, P. L. and Marsh, C. (eds.) Perspectives on Church-State relations in Russia, J.M. Dawson institute of church-state studies Baylor university, USA, 85-102.

Eshghi, S., Williams, G.-R., Colombo, G. B., Turner, L. D., Rand, D. G., Whitaker, R. M. and Tassiulas, L. (2017a), “Mathematical models

for social group behavior”, IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computed, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation, California, USA.

Eshghi, S., Williams, G.-R., Colombo, G. B., Turner, L. D., Rand, D. G., Whitaker, R. M. and Tassiulas, L. (2017b), “Stability and fracture of social groups”, 55th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing, Allerton, USA, 478-485.

Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K. and Britton, W. B. (2017), “The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists”, PLoS ONE, 12 (5), 1-38.

Oppy, G. (2018), Atheism and Agnosticism, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Whitaker, R. M., Turner, L. and Colombo, G. (2018), “Intra-group tension under inter-group conflict: a generative model using group social norms and identity”, Advances in Cross-Cultural Decision Making: Proceedings of the AHFE International Conference on Cross-Cultural Decision Making, Springer International Publishing,

167-179.

Wuthnow, R. (2007), America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA.