Traditional value orientation and religiosity – a multilevel analysis across Europe

Abstract

In this paper, we examine the relationship between traditional value orientation and religiosity in European societies. While the association between traditional values and religiosity is well-established, no study examined differences in its strength in relation to religiosity on a societal level. Our main aim is thus to test whether this association is moderated by country-level religiosity. Because of the weakened importance of religion in less religious societies, we hypothesized that the effect of religion on individual values is also weaker compared to more religious societies. We used the European Social Survey data, from 2018, with 49,519 respondents from 29 countries. The data indicated a significant but very weak negative moderating effect of country-level religiosity on an individual religiosity and traditional values association. We discuss our findings in the light of the transformation of the traditional relationship between human values and religiosity, as well as a separation between religion and culture.

Introduction. Traditional values refer to the respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that one's culture or religion provides (Schwartz et al., 2012). They involve a group's need to preserve and honor cultural customs and principles (Abi-Hashem and Driscoll, 2013). Strong traditions define community standards and regulate social behaviors – shared experiences of a group are often expressed through symbols or practices that may take the form of religious rites, belief, or normative behaviors (ibid.). They symbolize the group's solidarity, express its unique worth, and contribute to its survival (Schwartz, 2012a). Also, especially in times of crisis, respect and adherence to these values serve to solidify cultural bonds and develop alliances for support and cohesiveness – societies have relied upon strong cultural bonds to provide coherence for survival and stability through history (Abi-Hashem and Driscoll, 2013).

According to Schwartz's typology of value orientations (Schwartz, 2012a), tradition values are (along with power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, conformity and security values) one of the ten basic value orientations. They are often measured using items such as “He thinks it's important not to ask for more than what you have. He believes that people should be satisfied with what they have”, “Religious belief is important to him. He tries hard to do what his religion requires”, “He thinks it is best to do things in traditional ways. It is important to him to keep up the customs he has learned”, and “It is important to him to be humble and modest. He tries not to draw attention to himself” (Schwartz et al., 2001).

The above definition and items clearly reflect strong ties of tradition values and religiosity. Many researches indicate that traditional values, compared to other nine basic values, have actually the strongest relations with religiosity (Schwartz, 2012b; Saroglou et al., 2004; Saroglou, 2008; Pepper et al., 2010; Schwartz and Huismans, 1995; Schnabel and Grötsch, 2015). Schwartz and Huismans (Schwartz and Huismans, 1995) note some presumptions on the basis of which these findings may be explained. First, as religiosity emphasizes reaching toward and submitting to forces beyond the self, it should correlate positively with values that emphasize submission to transcendental authority by accepting the customs and beliefs of traditional culture. Second, religion symbolizes, preserves, and justifies the prevailing social structure and normative system – it encourages believers to accept the social order and discourage questioning and innovation, which is why religiosity should correlate positively with values that emphasize preserving the status quo. Third, as one of the functions of religion is individual's need to reduce uncertainty, religiosity should correlate positively with values that emphasize attaining and maintaining certainty in life.

Although the association between tradition and religiosity is well-established, examinations of differences in its strength in relation to religiosity on a societal level are non-existent. We fil the gap by testing these differences across European countries – which are still relatively heterogeneous in terms of religiosity (Van der Noll et al., 2018; Storm, 2017). We hypothesize that societal level religiosity moderates the association between individual religiosity and traditional value orientation – given that in less religious societies, religion should have a weaker role in an individual's behavior, attitudes, everyday life etc. (and thus value orientations as well).

Methodology and methods. We used the data from the European Social Survey, which is a large nationally-representative, repeated, cross-sectional survey in more than thirteen European countries. For the purposes of this research, we used the data form the ninth round of the survey, from 2018. The round contains data from a total 49,519 respondents (51.4 % of females, Mage = 48.42, SDage = 19.02), coming from 29 countries.

Religiosity in the ESS is measured using three dimensions: self-rated religiosity, frequency of attending religious services apart from special occasions, and frequency of praying apart from at religious services. However, we limit this examination to the first one only. Schwartz and Huismans (Schwartz and Huismans, 1995) give several arguments for such an approach in this type of research. The first argument is that research has the primary interest in relating religiosity to general cultural attitudes and not in unravelling relations among the various components of religion. Second, if the sample consists of relatively heterogeneous groups (as in different country residence and religious affiliation), religious commitment needs to be operationalized through religiosity's common denominator (rather than its discrete dimensions). Third, as the authors note, many prior researches indicate that nationally representative samples generate a single religious factor. It may also be noted that the unidimensional approach much simplifies multilevel analysis.

This dimension of religiosity in the European Social Survey is measured using the question: “How religious would you say you are?”, where 0 means “Not at all religious”, and 10 means “Very religious”. Traditional values orientation is measured on two six-point scales. Respondents rate extent to each of the following descriptions are or are not like themselves: “It is important to him to be humble and modest. He tries not to draw attention to himself”, and “Tradition is important to him. He tries to follow the customs handed down by his religion or his family”. The response options range from 1 – “Very much like me”, to 6 – “Not like me at all” (we reversed the scale values). Internal consistency of the scale is low (Cronbach's alpha = .325), which may be explained by the small number of items and the fact that value encompasses different sub-constructs (Schwartz, 2003), however, it is reasonable to be used (Sortheix and Schwartz, 2017).

In our analysis, we controlled for age, gender and income. We transformed gender into a dummy variable, with females as the reference category. Income is measured through ten categories, from 1 (which is the first decile) to 10 (which is the tenth decile).

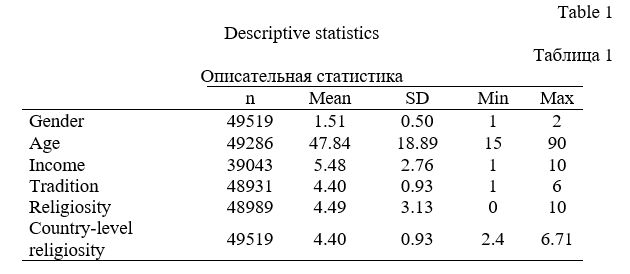

Research Results and Discussion. As it may be seen from Table 1, nearly 50000 respondents (from 29 European countries) rated their importance of tradition as 4.4 out of 6 on average, which indicates an above-neutral score. On the other side, the average self-rated religiosity score is to some extent below neutral – 4.49 on a ten-point scale. Country-level religiosity score – an average level of religiosity in all examined countries, is approximately equal (4,40).

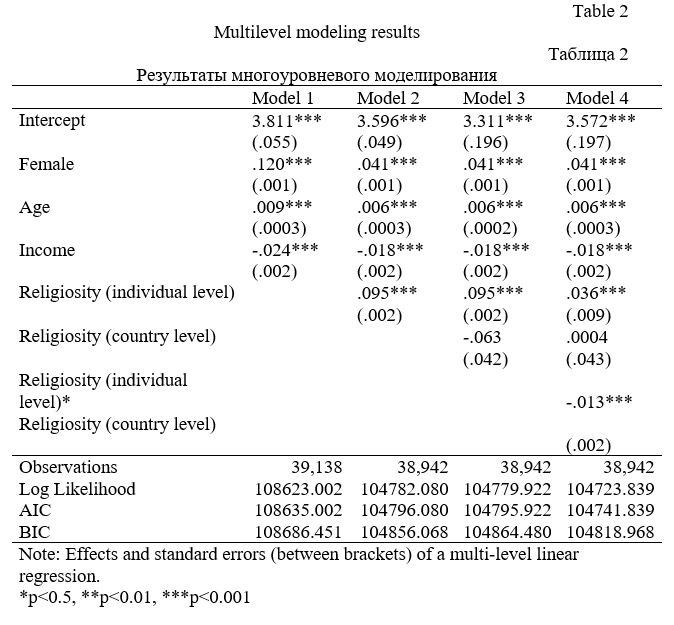

In order to examine whether more religious societies are characterized by the stronger effect of religiosity on traditional value orientation compared to less religious ones, we run four multilevel regression models. First of our models included only control variables (gender, age, and income). The second model additionally included individual religiosity. The third model included religiosity on a country-level, while the fourth includes an interaction effect of religiosity at a country-level and religiosity at the individual level on our dependent variable. The results of a multilevel regression are shown in Table 2.

The proportion in variation in tradition that lies between countries was approximately 6% - in the null model, the Intra-Class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was about .062. This indicates a clustering of observations within countries to the extent that multilevel models could to be applied. Our control variables have a significant, although weak, effect on traditional value orientation, especially income – which is slightly negative related to individual tradition values scores. Females have significantly higher scores of tradition value orientation compared to males. Age is also shown to be related to traditional values in a positive direction.

When it comes to our main independent variables, the results indicate a significant and positive association between individual religiosity and traditional values (Model 2). The effect is not very strong (β = .095), and religiosity on a country level is not related to individual traditional values (Model 3), which together indicate a somewhat separation of religion and tradition.

Finally, in order to investigate our main research question, we run a multilevel model on traditional values with an interaction effect between an individual-level and country-level religiosity – we tested whether religiosity on a country level moderates the relationship between religiosity and traditional values on an individual level (Model 4). The results indicated that country-level religiosity is a significant moderator of this association. The interaction is negative, although the effect is very weak.

Also, the goodness of fit measures (AIC and BIC) show that the fourth model explains the highest amount of variance compared to the previous three models.

In this paper, we carried out a multilevel analysis of traditional value orientation and religiosity across Europe. We found that tradition value orientation is related to age, lower income, and being female. This is consistent with many previous researches (Chan et al., 2020; Schwartz and Rubel, 2005; PEW, 2015). However, these effects are not strong. Having in mind items that the tradition scale is consisted of, it looks like the expectations within gender norms that woman should be humble and modest is still present across Europe, and on the other side, women usually experience less security in their lives, being more vulnerable to the hardships of poverty, debt, poor health, old age, and lack of physical safety (Norris and Inglehart, 2004; 2008; Kregting et al. 2019). The latter may also explain income differences in tradition values and religiosity. Older people may be more traditional and religious because they are more aware of their own mortality and the potential afterlife; also, in times they were socialized, traditional and religious practices were more common; finally, people who have become more isolated and disengaged from wider society may often find social network and support in traditional and religious groups (Voas and Crockett, 2005).

Conclusions. Our primary aim was to test whether in more religious societies across Europe the effect of religiosity on tradition is stronger than in less religious ones. We assessed the interaction effect of mean religiosity at a country-level and religiosity at the individual level on tradition. The results indicated that there is a significant negative, but very weak interaction effect. In other words, the level of religiosity on a country level does moderate, but to a very small extent, the association between individual religiosity and tradition values. Our results also indicate a moderate association between religiosity and traditional values on an individual level, and a non-significant effect of country-level religiosity on individual traditional values, so a weak moderating effect is not surprising.

Carneiro and colleagues (Carneiro et al., 2021) sum some explanations for the autonomy of value orientations in relation to religiosity and only moderate relation between them. To some extent, that can be somewhat related with the thesis that the traditional relationship between human values and religiosity is experiencing a transformation (see: Davie, 1990), which is, however, no evidence of ongoing secularization, but that people believe without belonging. This is a result of a rising religious pluralism, globally and particularly in Europe. Besides that, these authors agree with the thesis about advocating a pure religion and a separation between religion and culture (see: Roy, 2014). According to this thesis, there is no more a quest for synthesis or integration of religion and culture since religion was not concerned with society.

Future studies should examine the moderating effect of country-level religiosity in non-European countries, in the first place, more religious ones. Also, future research should examine these effects taking into account other dimensions of religiosity such as attending religious services or frequency of prayer.

Reference lists

Abi-Hashem, N., and Driscoll, E. G. (2013), “Values (Shalom H. Schwartz) – Power”, in The Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1324-1325.

Carneiro, A., Hélder F., Dinis, M., and Leite Â. (2021), “Human Values and Religion: Evidence from the European Social Survey”, Social Sciences, 10, 75.

Chan, S. W. Y., Lau, W. W. F., Hui, C. H., Lau, E. Y. Y., and Cheung, S.-F. (2020), “Causal relationship between religiosity and value priorities: Cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations”, Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12 (1), 77-87.

Davie, G. (1990), “Believing without belonging: Is this the future of religion in Britain”, Social Compass, 37, 455-69.

Kregting, J., Scheepers, P., Vermeer, P., and Hermans, C. (2019), “Why Dutch women are still more religious than Dutch men: Explaining the persistent religious gender gap in the Netherlands using a multifactorial approach”, Review of Religious Research, 61 (2), 81-108.

Norris, P. and Inglehart, R. (2008), “Existential security and the gender gap in religious values”, Shah, T., Stepan, A. and Toft, M. (eds.), Draft chapter for the SSRC conference on religion and international affairs, New York, USA.

Norris, P. and Inglehart, R. (2008), Sacred and secular. Religion and politics worldwide, University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Pepper, M., Uzzell, D., and Jackson, T. (2010), “A study of multidimensional religion constructs and value in the United Kingdom”, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49, 127-146.

PEW (2014), “Religious tradition by household income”, Available at: https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/compare/religious-tradition/by/income-distribution/ (Accessed 05 April 2021)

Roccas, S., and Sagiv, L. (2010), “Personal Values and Behavior: Taking the Cultural Context into Account”, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4 (1), 30-41.

Roy, O. (2014), Holy Ignorance: When Religion and Culture Part Ways, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Saroglou, V. (2008), “Religion and psychology of values: “Universals” and changes”, in Agazzi, E. and Minazzi, F. (eds.), Science and ethics: The axiological contexts of science, Peter Lang, Brussels, Belgian, 247-272.

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V., and Dernelle, R. (2004), “Values and religiosity: a meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model”, Personality and Individual Differences, 37 (4), 721-734.

Schnabel, A. and Grötsch, F. (2015), “Religion and Value Orientations in Europe”, Journal of religion in Europe, 8 (2), 153-184.

Schwartz, (2012b), “Values and Religion in Adolescent Development”, in Tromsdorff, G. and Chen, X. (eds.) Values, Religion, and Culture in Adolescent Development, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, 97-122.

Schwartz, S. H. (2003), “Proposal for measuring value orientations across nations”, in Questionnaire development report of the European Social Survey, Available at: http:// naticent02.uuhost.uk.uu.net/questionnaire/chapter_07.doc (Accessed 05 April 2021)

Schwartz, S. H. (2012a), “An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values”, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1).

Schwartz, S. H., and Huisman, S. (1995), “Value Priorities and Religiosity in Four Western Religions”, Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(2), 88-107.

Schwartz, S. H., and Rubel, T. (2005), “Sex differences in value priorities: Cross-cultural and multimethod studies”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 1010-1028.

Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., Fischer, R., Beierlein, C. and Konty, M. (2012), “Refining the theory of basic individual values”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 663-688.

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., and Owens, V. (2001), “Extending the Cross-Cultural Validity of the Theory of Basic Human Values with a Different Method of Measurement”, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 519-542.

Sortheix, F. M., and Schwartz, S. H. (2017), “Values that Underlie and Undermine Well-Being: Variability Across Countries”, European Journal of Personality, 31 (2), 187-201.

Storm, I. (2017), “Does Economic Insecurity Predict Religiosity? Evidence from the European Social Survey 2002-2014”, Sociology of Religion, 78(2), 146-172.

Van der Noll, J., Rohmann, A., and Saroglou, V. (2018), “Societal Level of Religiosity and Religious Identity Expression in Europe”, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(6), 959-975.

Voas, D., and Crockett, A. (2005), “Religion in Britain: Neither Believing nor Belonging”, Sociology, 39(1), 11-28.